Source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/flag-of-Bangladesh

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_symbols_of_Bangladesh

Source: https://www.un.orggeospatialcontentbangladesh-0

1. INTRODUCTION TO THE COUNTRY: BANGLADESH

Bangladesh, officially the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most-populous country in the world, with a population of around 165.1 million people in an area of 148,460 square kilometres. Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries in the world, and shares land borders with India to the west, north, and east, and Myanmar to the southeast; to the south it has a long coastline along the Bay of Bengal. It lies very close to Nepal, Bhutan, and China. Geographical position of the country makes it vulnerable to occasional natural disasters often forcing people to leave their homes.

Politics of Bangladesh takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the Prime Minister of Bangladesh is the head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament. The Constitution of Bangladesh was written in 1972 and has undergone seventeen amendments. The three major parties in Bangladesh are the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Bangladesh Awami League and Jatiya Party. The current prime minister is Sheikh Hasina, leader of the Bangladesh Awami League, who was sworn-in by the president on 6 January 2009 following the general election on 29 December 2008. The country suffered successions of political turmoil which sometimes spurred people’s decision to take refuge abroad.

The economy of Bangladesh hinges on three pillars: agriculture, garments and remittance sent by the migrant workers. Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan in 1971 when the country was one of the poorest in the world. However, the early 1990s marked large-scale trade liberalization followed by high economic growth in the 2000s, mitigating the poverty situation in the country to a large extent—poverty declined to 14.3 percent in 2016 from 43.5 percent in 1991 (based on the International poverty line of US$ 1.90 per day using the 2011 Purchasing Power Parity exchange rate). Despite this, economic inequality has been on the rise in Bangladesh since the 1980s, and as of 2021, only 1 percent of the population holds 16.3 percent of the country’s national income. The country had graduated from a low-income country to a lower middle-income country in 2015 and is on track to make it to the list of least developed countries by 2026, en route to its vision of becoming a developed country by 2041. (Wikipedia)

Labour migration from Bangladesh has its roots since independence. Immediately after independence, the country experienced extremely fragile economy. People suffered stark poverty, faced stark starvation and sordid reality. Both these curses prompted them to look for a new lease of life beyond the borders of the country – a life full of expectation, good salary and social security free from financial destitution and life threat. Other drivers include natural calamities, political unrest, violence, conflict, lack of employment opportunities, low salary and income, etc. Aspirant people started to make their ways outside the country for work and set their destinations mainly in the Middle Eastern countries. Each year, more than 700,000 migrant workers leave the country for overseas employment. Problems faced by Bangladeshi migrants include: high fees for migration charged by recruiting agencies, especially for low skilled jobs; low wages, lack of information on migration opportunities and risks; discrimination, exploitation and abuse while overseas; and insufficient services to protect the rights of migrant workers.

Overseas employment plays an instrumental role in easing the pressure on the domestic labour market. With more than 2 million people entering the labour force annually during recent times, the current rate of economic growth in Bangladesh has not been able to create employment quickly enough to fully absorb new workers. Training young aspirant people in trades on demand, making them skilled, searching for new labour markets to accommodate these trainees and sending them abroad will spur the economy.

The contribution of labour migration to poverty alleviation is noteworthy, with remittances boosting household consumption and savings significantly. Families of migrants in Bangladesh can lead easeful life. They can make room for good food, lodging, education for children, good treatment when in dire need and so on. Remittances also have a positive impact on the balance of payments and help offset deficits in the balance of trade in goods and services.

Achievements in Labour Migration Governance

• Reopening of labour markets in some countries;

• Enactment of laws, policies and rules;

• Expansion of Labour Welfare Wings and Increase of Staff;

• Labour Market Analysis in 53 countries;

• Constructing Technical Traning Centres in Upazilla Level;

• Decentralization of some services related to overseas employment and welfare of migrants and their family members;

• Developing awareness-raising mechanisms and increasing campaigns;

• Hosting of Global Forum on Migration and Development;

• Signing of Global Compact for Migration;

• Inclusion of migration in Five-Year plan and SDG agenda

Challenges in Migration Governance

• Irregular Migration

• High Migration Cost

• Intervention of Middlemen

• Aspirant Migrants Falling Victims to Traffickers and Smugglers

• Forced Repatriation or Expulsion of Irregular Migrants

• Timely Issuance and Delivery of Passports

• Expansion of Expatriate Welfare Bank

• Illegal Transfer of Remittances

• Dissemination of Accurate and Updated Information

• Decentralisation of Services

• Recruitment Directly by Recruiting Agencies

• Selection of Migrants from BMET Database

• Poor Staffing at Technical Training Centres (TTCs) and District Employment and Manpower Offices (DEMOs)

• Expansion of Labour Welfare Wings and Increasing Staff

• Absence of Branch Offices of Travel and Recruiting Agencies

• Lack of Monitoring and Supervision of Recruiting Agencies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki

2. MIGRATION STOCKS

2.1 Immigrant Stocks

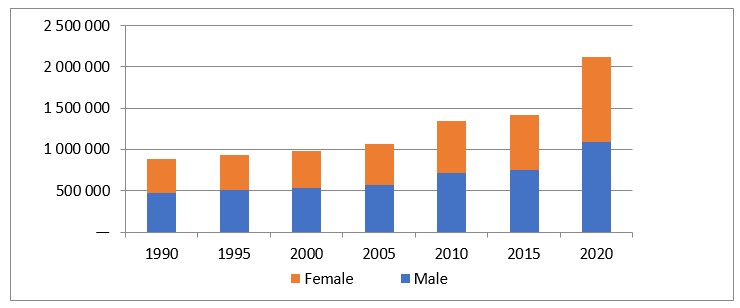

Figure 2: Over time (1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020) disaggregated by sex

Source: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

Figure 2 presents information regarding the proportion of male and female international migrants coming into Bangladesh over a period of 30 years. It shows a significant growth from 1990 to 2020. The proportion of male and female immigrants is more or less equally balanced.

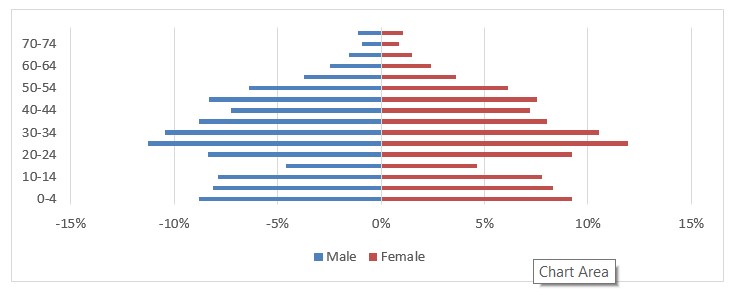

Figure 3: Most recent year (2020) disaggregated by sex and age group

Source: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

The above figure demonstrates data regarding foreign-born population coming into Bangladesh in accordance with the sex and age groups in the year 2020. The proportion of male and female immigrants is much the same in age groups 0-19 and 35 onwards. But in the age groups between 20 and 34, there is an increase of female international migrants in Bangladesh.

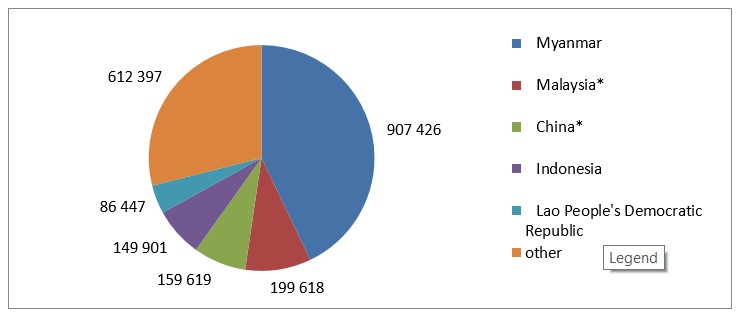

Figure-4: Most recent year (2020) top countries of origin

The figure 4 below presents the top countries of origin of international migrants coming into Bangladesh in 2020. It figures out that most immigrants entered into Bangladesh from Myanmar followed by Malaysia, China, Indonesia and Lao People’s Democratic Republic. But in reality, there are a significant number of people from India, Korea, Sri Lanka, Japan and Thailand working in Bangladesh.

Source: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

2.2 Emigrant Stocks

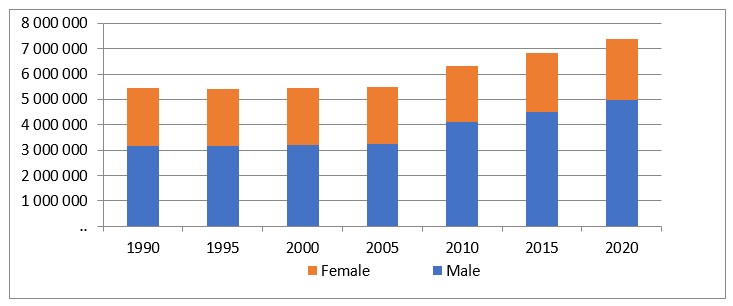

Figure 5: Emigrant Stocks from Bangladesh by Sex, 1990 – 2020

Source: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

The data presented in Figure 5 above show the proportion of male and female emigrants from Bangladesh over a period of 30 years from 1990 to 2020. From 1990 to 2005, the proportion is much the same. But since 2005, there is a noticeable increase of male emigrants nearly reaching the highest margin of 5000,000 in 2020.

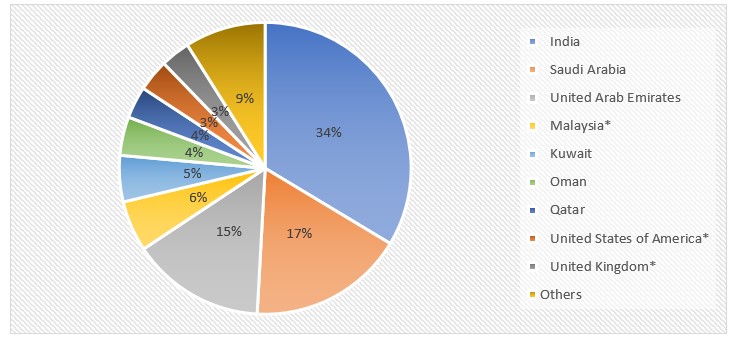

Figure 6: Most recent year (2020) top countries of destination

Source: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

The top countries of destination for Bangladeshi emigrants are presented in Figure 6. It shows that most chosen country of destination for Bangladeshis is India (34%) followed by Saudi Arabia (17%), United Arab Emirates (UAE) (15%), Malaysia (9%), Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, United States of America (USA) and United Kingdom.

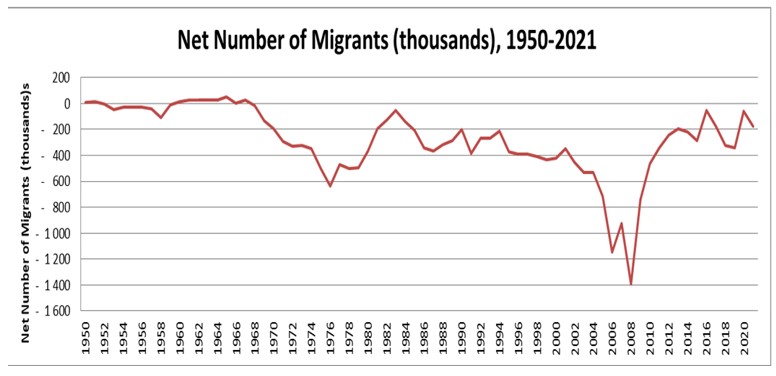

3. NET MIGRATION

The following figure 7 shows net migration in Bangladesh from 1950 to 2021. There are significant declines in the years 1976, 2006 and 2008 and increases in 1984, 2016 and 2020.

Figure 7: Net Migration of Bangladesh

Source:https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Migration/

4. MIGRATION FLOWS

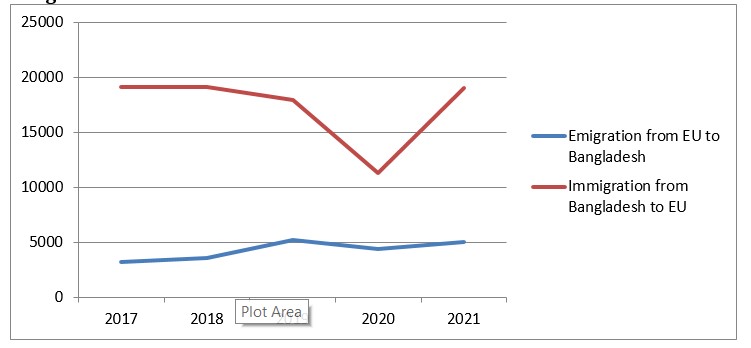

Figure 8: Immigration from Bangladesh to EU27 and Emigration from EU27 to Bangladesh

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home

The Figure 8 above presents a great number of Bangladeshis entering into EU countries every year and the year 2020 has the lowest entries of Bangladeshis into EU countries owing to COVID-19 pandemic. There is a steady increase in the number of EU citizens entering into Bangladesh and 2019 is the year when the highest number of EU citizens came into Bangladesh. There is downtrend in 2020 due to travel restrictions imposed by corona virus.

5. IRREGULAR MIGRATION: BETWEEN BANGLADESH AND THE EU

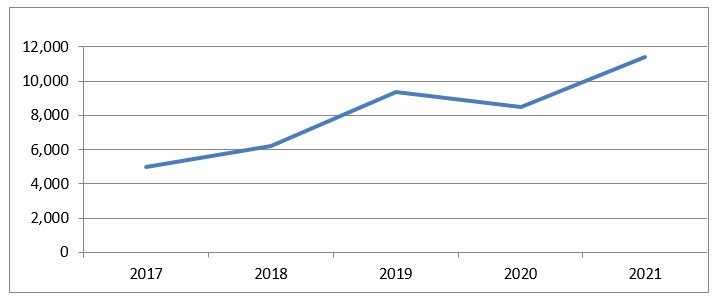

Figure 9: Third country nationals found to be illegally present – annual data

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home

The data shown in Figure 9 above clearly points out the growing number of illegal Bangladeshi migrants in the EU countries over a period of five years from 2017 to 2021. It also shows that the number is alarmingly spiraling to its peak in 2021.

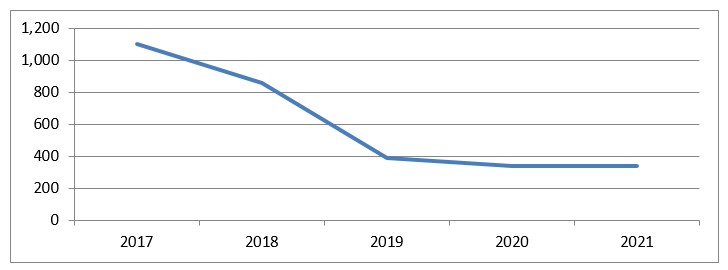

Figure 10: Third country nationals refused entry at the external borders – annual data

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home

The data in Figure 10 above clearly shows that the declining number of Bangladeshi migrants being refused entry at the external borders of the EU countries over a period of five years from 2017 to 2021. It also shows that the number is surprisingly diminishing to its nadir in 2021.

6. INTERNAL AND INTERNATIONAL DISPLACEMENT

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Bangladesh

The history of internal displacement in Bangladesh dates back to its independence in 1971 when almost a third of its population was displaced. However, since then, climate change and ethnic conflict have also contributed to internal displacement. Bangladesh currently places seventeenth out of the countries with the largest number of IDPs. As of 31 December 2021, there were a total of 427,000 IDPs in Bangladesh as a result of conflict or violence and approximately 99,000 IDPs as a result of disasters.

The geographical location of Bangladesh and high population density make it one of the world’s most disaster-prone countries. Disasters such as violent storms, cyclones, drought, landslides, riverbank erosion, salinity, water-logging and flooding are the main causes of displacement in the country, particularly during the June-September monsoon season.

According to IDMC, internal displacement due to conflict and violence has declined significantly from 6 thousand in 2017 to 151 in 2021. Internal displacement due to disasters has also decreased from 946,100 in 2017 to 98,800 in 2021 but with a tremendous upsurge in 2019 (4.1 million) and in 2020 (4.4 million).

Asylum Seekers in Bangladesh

Besides being a country of origin for many asylum seekers, there are also refugees from other countries, who apply for asylum in Bangladesh and hope for a better future. In the year 2021, there have been 26 asylum applications from Somali and 5 asylum applications from Afghan refugees in Bangladesh. (Worlddata.info, UNHCR)

Refugees in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the most refugee hosting countries in the world. According to UNHCR data, as of 2021, the country hosts 918,907 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. More than 700,000 of these refugees fled genocide, persecution, large-scale violence and human rights violations by the Myanmar military in August 2017 and took shelters in neighboring state Bangladesh. Five years have passed and there are no immediate solutions on the cards resulting in a protracted humanitarian crisis. This prolonged displacement and uncertainty about the future of the Rohingya and their return is a major cause of concern for all. Moreover, the Rohingya refugees have been accommodated in the camps in Cox’s Bazar district and many have been relocated to Bhashan Char. They are provided with the bare necessities of life such as protection, food, water, shelter, health care and education by the government of Bangladesh, supported by international donors and humanitarian actors.

According to the UNHCR data, the refugee population in Bangladesh has remarkably increased over the last 10 years from 2012 to 2021. In 2012, the number was 230,700. There had been almost no change until 2015 but in 2016 the number of refugees went up to 276,200. In 2017, the number changed dramatically to reach an astonishing figure 932,210 when people from Myanmar crossed border to save lives. (UNHCR)

International Obligations on Bangladesh

Even though not a signatory to the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol or the UNHCR Statute, Bangladesh has ratified a number of major international human rights instruments. Among them the significant ones are the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); Four Geneva Convention of 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC); Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); Convention Against Torture (CAT) etc. All of these instruments have a far-reaching bearing on Bangladesh’s obligation to protect refugees. However, in reality, the international human rights are not enforceable in courts of law unless, specific provisions are incorporated into existing municipal laws or given effect through separate legislations.

The legislations which are used for dealing with refugees are: The Foreigners Act, 1946; The Foreigners Act, 1946; The Foreigners Order, 1951; The Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939; The Registration of Foreigners Rules, 1966; The Passports Act, 1920; The Passport Rules, 1955; The Bangladesh Passport Order, 1973; The Citizenship Act, 1951; The Bangladesh Citizenship (Temporary Provisions) Order, 1972; The Bangladesh Control of Entry Act, 1952; The Extradition Act, 1974; The Naturalization Act, 1926; The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908; The Children Act, 1974

In the absence of any legal or specialized statutory frame work for the protection of refugees, Bangladesh relies on these acts to govern the entry, stay and exit of foreigners in Bangladesh.

Section 2(a) of the Foreigner Act defines a foreigner, as a person who is not a citizen of Bangladesh, thus covering all refugees within its ambit as well. Section 3 of the Foreigner Act 1946, empowers the Government to enact rules regarding the banning or controlling of the entering, staying and leaving of the foreigners in Bangladesh. Section 4 of the same Act specifically provides that any foreigners can be intervened in a limited space vide this Act. (DU & International Journals)

Protection of Refugees under the Constitution and the way-forward

The asylum seekers from other countries are granted refugee status by the Government of Bangladesh under “Executive Order”. For example, during 1978 and the time between 1991 and 1992, the Rohingya asylum seekers from Myanmar, were provided refugee status under Executive orders of the Government of Bangladesh. They were granted prima facie refugee status. During the refugee influx from 1991 to 1992, the Government invited the International Refugee Agency UNHCR to launch its humanitarian operation in Bangladesh. The Government also allowed both national NGOs and international agencies to assist the refugees.

The Government of Bangladesh has taken the refugee issue on humanitarian ground. Civil society organizations, NGOs, political leaders, policy makers, and media personnel have raised the issue of refugee protection and the need for a comprehensive legal or institutional structure to protect and promote the basic rights of refugees in Bangladesh. Therefore, Bangladesh should urgently need to formulate a national legal framework on refugee to develop an adequate and effective protection mechanism to deal with complex refugee crisis at ease. In this connection, the signing of the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol by Bangladesh will surely provide a legal framework and certain rights to the refugees in the country. However, going beyond the box, the administration at various levels must have the ‘will’ to help one of the most disadvantaged groups in the world. (DU & International Journals)

7. REMITTANCES

Remittance has become a stepping stone in the shaping of spiraling growth of the economy of Bangladesh. The national economy and migrants’ families are highly dependent on the regular financial transfers by migrants, and they are thus vulnerable to ruptures of the money flows. Ninety percent of the money that is being sent to Bangladesh by its migrants and the diaspora comes from ten countries Saudi Arabia, UAE, the US, Kuwait, the UK, Qatar, Italy, Malaysia, Oman and Bahrain, 58 percent from the Gulf States alone. (BMET)

Bangladesh reached a new record in remittance, despite the global financial turmoil caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The country received remittance worth $18.21 billion in the fiscal year 2019-20, which is 9.6% higher than the previous year, according to official figures. In fiscal year 2018-2019, the country had received $16.4 billion and $14.98 billion in 2017-2018. (BMET)

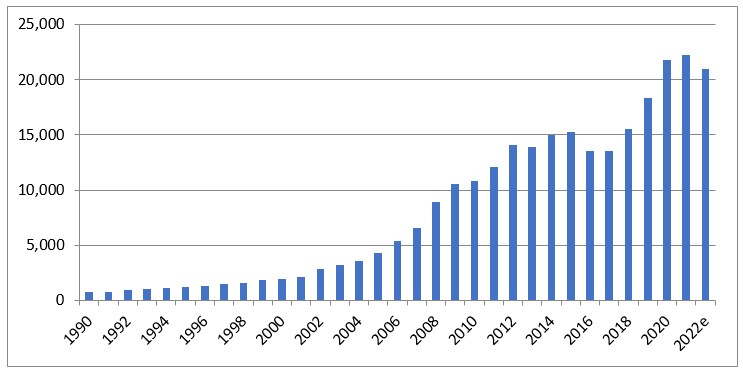

The data of the following figure 11 show a steady growth of remittances coming into Bangladesh from 1990 to 2022. Remittances reached the landmark of 15,000 million USD in 2014 and 2015 followed by a small two-year decline in 2016 and 2017, then the growth gained ground and reached its peak in 2021.

Figure-11 Remittance inflows in Bangladesh (USD millions)

Source: https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

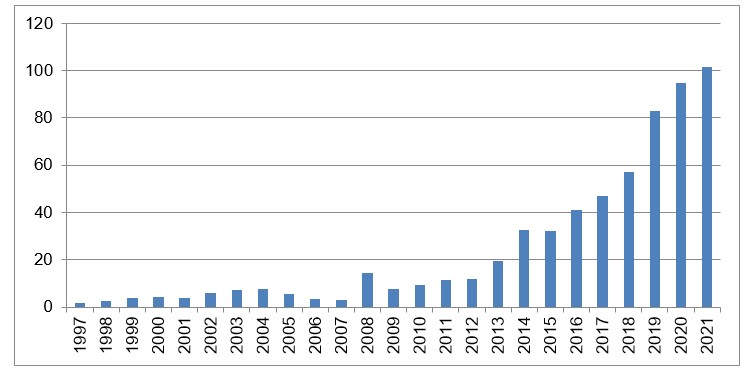

The figure 12 below shows remittance outflows from Bangladesh. There is no data available from 1990 to 1996. Since 1997, there were ups and downs of the outflows until 2016 but from then on there was a steady growth culminating in 2021.

Figure-12: Remittance outflows from Bangladesh (USD millions)

Source: https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

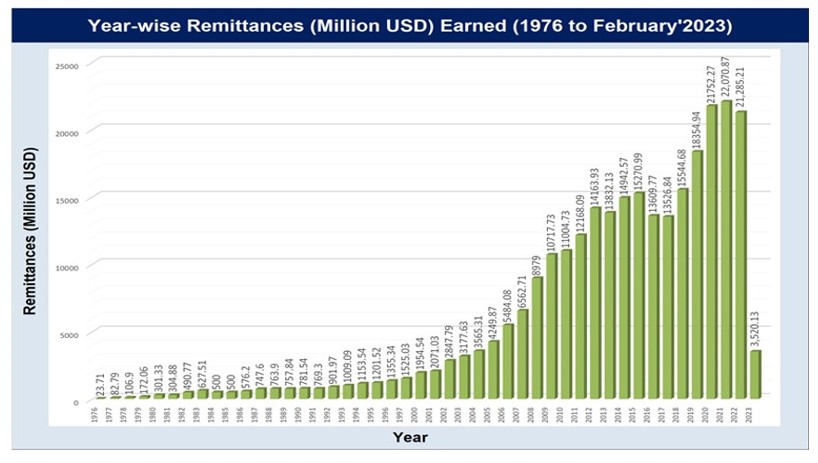

The following figure 13 presents national remittance inflows data from Bangladesh Bank and Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET). BMET preserves these data since its establishment in 1976 till date. It is evident that the inflow data presented by both national and international sources are noticeably congruous. There is no obvious disparity in between.

Figure-13: Remittance inflows in Bangladesh (National data)

Source: http://www.bmet.gov.bd/site/page/1baff8ec-27eb-48e0-9ec6-1751cd5411d8/-

But no outward remittance data is found in any national sources. There is a big gap of data on emigrant and immigrant stocks, flows, net migration, irregular migration and outward remittances in the national level. Bangladesh Bank and BMET have data on remittance inflows and emigrants respectively. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics has internal labour data but it preserves migration data from BMET.

Source: http://www.bbs.gov.bd/site/page/111d09ce-718a-4ae6-8188-f7d938ada348/-

REFERENCES

1. https://www.britannica.com/topic/flag-of-Bangladesh

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_symbols_of_Bangladesh

3. httpswww.un.orggeospatialcontentbangladesh-0

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki

5. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/bangladesh-economy-strong-points-and-red-flags/

6. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

7. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Migration/

8. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home

9. https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

10. http://www.bmet.gov.bd/site/page/1baff8ec-27eb-48e0-9ec6-1751cd5411d8/-

12. https://www.bb.org.bd/en/index.php/econdata/wageremitance

13. https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/Bangladesh

14. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download/?url=f8wzj7

15. https://www.worlddata.info/asia/bangladesh/asylum.php

16.https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2022/12/12/hope-amid-despair-finding-solutions-for-rohingya-in-bangladesh

17. http://www.mcrg.ac.in/rw%20files/RW39_40/12.pdf

18. Dhaka University Law Journal, Studies Part-F Vol. XVIII (1): 109— 130 June 2007

19. International Journal of Ethics in Social Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2018

Written by

DEBABRATA GHOSH

Assistant Director

District Employment and Manpower Office (DEMO), Cumilla

Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET)

Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment